As an emergency physician with an interest in humanitarian medicine, my career has allowed me to scrutinise diverse health systems across three continents. I am most familiar with the National Health Service of the United Kingdom, having gone through the specialty training process to earn my fellowship of the Royal College of Emergency Medicine. However, my undergraduate and formative years as a young doctor were in Bangladesh where I too went through a structured training process. My recent deployments with Doctors Worldwide have given me access to the primary healthcare systems of Malawi and Rwanda, where we have conducted training as part of the health system strengthening process. There are many areas that one can focus on to compare and contrast between these different systems but for the purpose of this exercise, we will take a deep dive into the andragogical processes that I have been an integral part of.

Although Knowles developed the Adult Learning Theory back in 1968, there has been great disparity in its use in educational systems in the East and West. The West recognised that adults learn differently than children and took the principles of andragogy and developed them further to come up with the ideas transformational, experiential and self-directed learning, among many other techniques. In my personal experience, the majority of South Asian countries retained the process of teaching in a didactic manner well into the new millennium. Training needs assessment for our projects in Africa have revealed that didactic teaching is still the norm for healthcare professionals.

Having transferred between learning systems myself and being in a position to create training programmes for a broad spectrum of learners, I find myself often reflecting on how applicable adult learning principles are across different cultures. Some of the established principles of adult learning are listed and explained below:

- Self-direction: Adults want to be involved in planning, delivering, and executing their learning. They prefer to set their own learning objectives, choose their methods and resources, and assess their own progress.

- Relevance: Adults want to know how new information is relevant to them and how it will help them solve problems or perform better at work.

- Real-world application: Adults are more likely to learn when they can apply new information immediately to real-world situations.

- Multisensory learning: Adults are more likely to remember information if it is presented in multiple ways and reinforced through multiple senses.

- Prior experiences: Adults draw on their personal and professional experiences to help them understand new information.

- Goal-oriented: Adults are focused on achieving goals and practical problem-solving.

- Open to new methods: Adults are open to modern ways of learning and different methods and schedules.

- Stress: People learn best under low to moderate stress.

- Readiness: Adults are more likely to engage in learning activities when they perceive a direct relevance to their lives.

Although the list above is not exhaustive, it is a good representation of the paradigm of andragogy. As an organisation that delivers training on selective and specialist topics, our training needs assessments do ensure that we adhere to the principles of relevance and goal-orientation. Although the requirements for these particular principles transcend culture, it is interesting to note how sought after relevant training is in developing health systems where training is scarce, as opposed to the multitude of options available in the western systems. My intrigue predominantly lies in the application of self-direction, multisensory learning, prior experiences and openness to new methods in naive learning environments.

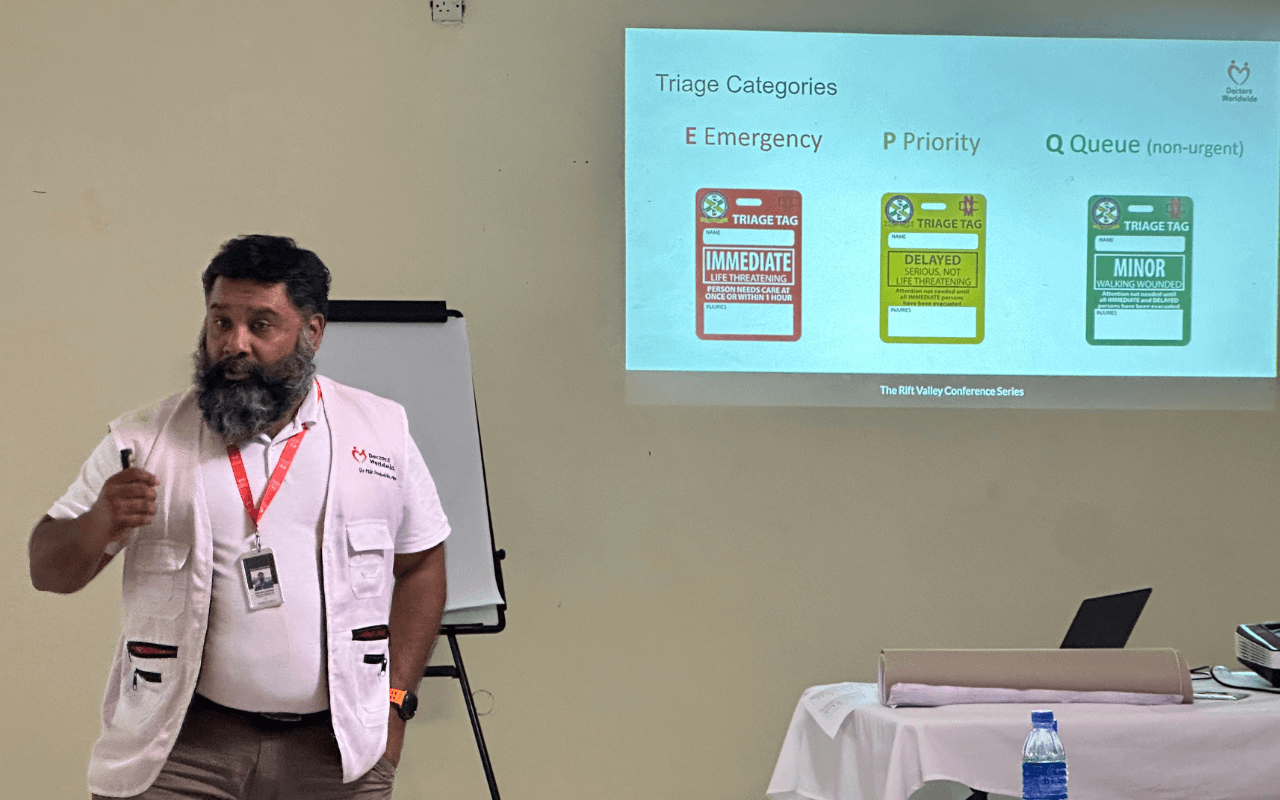

Before we run a training programme anywhere in the world, we pilot the programme to test participants’ openness to new methods of learning. While retaining didactic elements, we introduce role playing, clinical scenarios, workplace based assessments and tabletop exercises as new modalities. Invariably, participants take to these tasks quite comfortably having had ice-breakers and briefing sessions. In Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, while running our Postgraduate Fellowship in Refugee and Migrant Health during the Rohingya Crisis, our table-top exercise allowed the young, newly recruited doctors manning the primary healthcare facilities to understand the intricate dynamics of the health cluster and the roles of all the actors on the ground.

Multisensory learning in the form of simulation training works very well as long as the simulated environment reflects the participants’ work environment, rather than running from a pre-made script meant for a different health system. Using low-fidelity simulation for Basic Life Support in Blantyre, Malawi, where the participants were lay professionals, triggered an in depth discussion into the ethics of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation in a low resource setting.

Self-directed learning can be ‘hit and miss’. If left to their own devices, participants will often fail to deliver on such topics. However, keeping goal orientation in mind, when self-directed learning is coupled with a certificate of accreditation and a deadline, it proves to be a valuable resource. We are currently in the process of creating a multi-level curriculum for palliative care in Kigali, Rwanda for a variety of grades of healthcare professionals. A planned training of trainers’ session with our partner on the ground will allow them to direct the pace of these training sessions for future volunteers and care providers.

Reflecting on current and prior experiences can be a strong tool for learning. It allows a participant to delve into the evidence-base of a subject matter, an aspect of learning often overlooked and replaced by rote memorisation. Although initial prompting and coaching has been required for participants, once the entire group gets involved, the discussions start flowing. A mentoring session in the Rohyingya camp led to a profound experience for a young, male doctor, which we discussed upon reflection. A young, recently bereaved widow had attended and the ante-natal nurse asked the doctor to see her as the patient had been wrongly triaged to the nurse. The patient was dressed in a traditional abaya, and had attended as she was experiencing discharge. In what was clearly a very brief and uncomfortable consultation for the doctor, he immediately prescribed antibiotics for a presumed pelvic inflammatory disease. As part of the mentoring process, I asked the doctor to take a detailed history, including a sexual history, and the doctor was clearly taken aback, stating that this was culturally not appropriate. When explained that all relevant history can be obtained by good communication techniques, both verbal and non-verbal, and after being coached through the process, the doctor was surprised that the patient offered all the information he required without being offended. Antibiotics were not required, the patient left satisfied and the doctor realised he had been placing limitations on himself, when none existed.

In my experience, I have not found any of the participants we have trained to be uncomfortable adapting to new learning environments. There are the times when behaviours and strategies meant for one healthcare service are transposed upon another, rather than transferring the principles of learning, but these are few and far between. Rather, using these modern principles of adult learning to run training with multiple cohorts of healthcare professionals has allowed mentoring opportunities by developing a community of learning within the local region as well as the organisation. The bottom line is that appropriately applying the principles of adult education in new cultural contexts can be a very effective model with rewarding outcomes and long-term impacts, especially in under-resourced communities. .

In my experience, I have not found any of the participants we have trained to be uncomfortable adapting to new learning environments. There are the times when behaviours and strategies meant for one healthcare service are transposed upon another, rather than transferring the principles of learning, but these are few and far between. Rather, using these modern principles of adult learning to run training with multiple cohorts of healthcare professionals has allowed mentoring opportunities by developing a community of learning within the local region as well as the organisation. The bottom line is that appropriately applying the principles of adult education in new cultural contexts can be a very effective model with rewarding outcomes and long-term impacts, especially in under-resourced communities. .